- Ethnic African American

- Doll Complexion

- Doll Gender

- Doll Hair Type

- Doll Size

- Type

- Artist Doll (75)

- Baby Doll (18)

- Bracelet (6)

- Collectible (12)

- Doll (20)

- Doll Playset (14)

- Fashion Doll (137)

- Figure (9)

- Figurine (10)

- Hardcover (14)

- Necklace (8)

- Painting (91)

- Photograph (215)

- Play Doll (14)

- Porcelain Doll (22)

- Print (115)

- Rag & Cloth Doll (16)

- Reborn Doll (7)

- Sculpture (7)

- Textbook (40)

- Other (332)

- Unit Of Sale

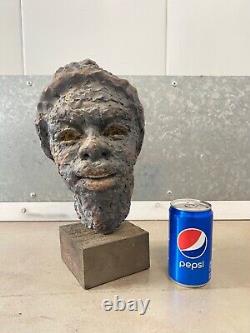

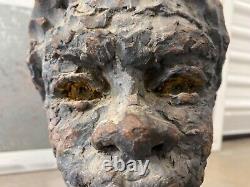

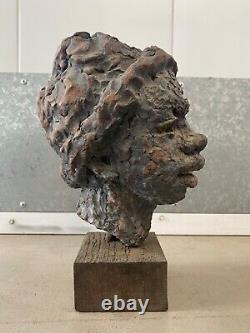

Antique Old WPA Black African American Harlem Renaissance Sculpture 1930s

This is an expressive and masterful Antique Old WPA Black African American Harlem Renaissance Sculpture, comprised of fired and hand molded clay, approximately dating to the 1930's - 1940's. This artwork depicts the portrait bust of a woman wearing a hat, with a slight smile on her face. Her facial features are rendered in a lifelike fashion, and the emotion depicted in her face could only have been created by a finely trained artisan. The story that I got with this item was that it was created by an African American New Deal artist during the WPA program.

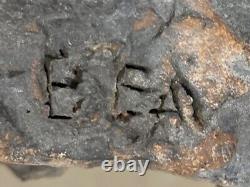

This piece is reminiscent of early sculptures by luminaries such as Elizabeth Catlett, Augusta Savage and Richmond Barthe. This work is signed: "BEA" or "BEAL" at the lower edge, but I have had no luck discovering the sculptor. Perhaps you know more about the artist or their work? Approximately 12 1/2 inches tall x 8 inches deep x 6 1/2 inches wide including stand. Acquired from an old estate in Pasadena, California.

If you like what you see, I encourage you to make an Offer. Please check out my other listings for more wonderful and unique artworks! What was the Harlem Renaissance? The Harlem Renaissance was an influential movement of African-American art, literature, music, and theatre. The movement emerged after the First World War, and was active through the Great Depression of the 1930s until the start of the Second World War.

Most of the artists associated with the movement lived and worked in the predominantly African-American neighborhood Harlem in New York, which became a great cultural hub flourishing with creativity. The artists associated with the Harlem Renaissance aimed to take control over representations of their own people, instead of accepting the stereotypical depictions by white people. They asserted pride in black life and identity, and rebelled against inequality and discrimination.

Identity, pride, agency, transformation, African American culture, African art, modernism, black avant-garde. Augusta Savage, Aaron Douglas, Hale Woodruff, James Lesesne Wells, Archibald John Motley, Beauford Delaney, Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller, James van der Zee, Palmer Hayden, Jacob Lawrence, Allen Lohan Crite. Historical and Social Context of the Harlem Renaissance. The Harlem Renaissance started after a summer of bloody race-related riots in 1919, known as the Red Summer.

It was half a century after the abolition of slavery, and lynchings were still common in the South, attempts to pass an anti-lynching bill in Congress were repeatedly refused, and white supremacy was widely accepted and reinforced by the prevailing cultural forces of contemporary books and movies. They had been treated with far more respect and equality whist away in France than they were used to back home. In the meantime, during the war years in Europe, half a million African-Americans had left the American South for industrialized Northern cities like New York, Chicago, Detroit, Columbus and Cleveland in search of employment and communities less rife with bigotry. In New York, the Harlem neighborhood had been planned for middle-class white families but had been overdeveloped, so many black families started moving there. The Different Disciplines of the Harlem Renaissance. A burgeoning black creativity began to arise in Harlem. Writers, artists, musicians and theatre practitioners inspired each other and often worked across disciplines, aiming for art that defied stereotypes and that fought against injustice and discrimination. Providing most of the intellectual grounding for the Harlem Renaissance was the philosopher, sociologist, writer, and patron of the arts Alain LeRoy Locke and his essay Harlem, Mecca of the New Negro.The essay introduced Harlem and its cultural boom to a wider public. He expanded on these ideas in his anthology of essays. (1925) which included his influential essay "The New Negro". The initial name of the movement, "The New Negro, " derives from this anthology and essay.

The essay called for a "new dynamic phase. Of renewed self-respect and self-dependence" in the community. Leading writers of the Harlem Renaissance include Langston Huges, Zora Neale Thurston, Arna Bontemps, Jean Toorner and Claude McKay.

Langston Hughes wrote the brilliant poem "I, too" (1926), which demonstrates a yearning and demand for equality. / They send me to eat in the kitchen / When company comes, / But I laugh, /And eat well, /And grow strong. / Tomorrow, / I'll be at the table / When company comes. / Nobody'll dare / Say to me, / "Eat in the kitchen, " / Then.

In terms of music, the popularity of jazz spread more and more, with musicians like Billie Holiday, Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington associated with the Harlem Renaissance. In theatre and performance, great actors like Paul Robeson and Josephine Baker were making their mark. In the visual arts, artists portrayed African American life, taking agency over the portrayal of their own people. Moreover, it was an avant-garde movement where artists were experimenting and allowing themselves a vast variety of influences, including, for example, the European modernists. The Visual Arts of the Harlem Renaissance.Sculptors, painters and printmakers were key contributors to the Harlem Renaissance. Aaron Douglas, who is sometimes referred to as "the father of African American art", was an important figure in the movement, who defined a modern visual language representing black Americans in a new light.

In his cycle of four murals, "Aspects of Negro Life", commissioned by the Public Works of Art Project to decorate the section of the New York Public Library intended for research into black culture, Douglas combined imagery from African-American history with scenes from contemporary life, fusing the influences of African sculpture, jazz music and geometric abstraction. Douglas was influenced by modernist movements such as Cubism, and he and other artists also found a great source of inspiration in West Africa, in particular the stylized sculptures and masks from Benin, Congo and Senegal. They viewed this art as a link to their African heritage.

Many artists also turned to the art of antiquity, especially Egyptian sculpture. One of these artists is Meta Warrick Fuller, a female sculptor who became a protégé of Auguste Rodin in Paris, before returning to work in the United States. (1921), was inspired by the period of the Pharaohs in ancient Egypt, and is widely considered the first Pan-African American work of art.

Her sculpture was an allegory for the musical and industrial contributions of African Americans to the development of the United States. Printmakers James Lesesne Wells and Hale Woodruff explored a streamlined approach, drawing from African and European artistic influences.They worked with block printing, lithography and etching, creating a distinctive visual language and making a mark with their inventive, modern printmaking. Photography was also an important element in the Harlem Renaissance.

The most iconic photographs capturing this art movement, this very specific time and place, were taken by photographer James Van Der Zee. He recognized the incredible richness of the intellectual and artistic life in Harlem during those years, and realized he had to capture it on film. Van Der Zee produced thousands of photographs of and for Harlem's flourishing middle class. He took both formal, posed photographs in his studio, and photo essays of street scenes, cabarets, restaurants, barbershops and church services.

His images immortalize the story of this thriving artistic community. The Legacy of the Harlem Renaissance. The Harlem Renaissance left a huge legacy. For one, the stars of the next African American artistic generation, like Romare Bearden, Norman Lewis and Jacob Lawrence, were taught by Augusta Savage, a key figure of the Harlem Renaissance.

Furthermore, the movement inspired generations of black artists to come. In the words of Wil Haygood. Were it not for this movement, other art movements may not even have sprung up. The Harlem Renaissance gave women, gave impoverished people all over this country a hint of just what you can do if you want to put your art on the line, because all they really wanted was to show America that, if you give us a fair chance, we will produce greatness. From that movement they have stitched, the black American, forevermore, into the artistic fabric of this country.